|

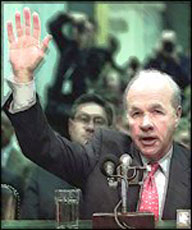

| For days, I have been thinking about my editor Jason Stern's interview with Joel Kovel published in last month's Chronogram. We were, in that conversation, offered a relatively rare perspective on the inner nature of capitalism, a word, which, as I type it, seems to have an archaic quality, as though it were referencing an accusation long ago proven false. Images of my shaggy-haired classmates in the 70s and 80s deriding evil still come to mind; you know, Meathead getting down on the system, anarchists meeting in the basement of the student union, and drones handing out Worker's World in Greenwich Village. It's like, if you even bring up the whole issue of capitalism, then you must be a terrorist or at least a communist, or their close cousin, environmentalist (note that, in an interesting geosynchronicity, we are incarcerating alleged terrorists on our military base leased from a communist and environmentalist country, our arch-enemy, that great threat to freedom, Cuba). Capitalism is not a real issue, it's just this thing we all have to live with. Everyone knows we cannot bite the hand that feeds us. As Al Gore explained in Earth in the Balance (referenced in this column in November 2000), we cannot call our system of business and governance dysfunctional for the same reasons a child can't mention that his parents are negligent, abusive or incompetent: they have the power to cast him off. Hence, Al explained, we, collectively, refuse to say there is a problem, because we think we would be rejecting our very source of sustenance by doing so. In being silent, we actually take the problem on, which is meaningless because we cannot solve it. So we internalize it and commence denial mode simultaneously. There is no problem. Everything is fine. Any individual with a problem is the problem. If you say, for example, that cancer keeps cancer drug makers in business and that's why it's never cured (does everyone know that chemotherapy can cost $5,000 per week?), or if you say college dormitories are contaminated with dioxin, or if you say that the 'war on terror' (and I still cringe every time I hear those words) is really a business deal designed to spread the hegemony of the West, smash civil rights and take over oil reserves in western Asia, you are a conspiracy theorist freak, and worse, you're angry, and you should know better. Know better? Everyone knows that cigarette and asbestos manufacturers hid the dangers of their products. Everyone knows that Nixon knew, and that Reagan knew, and that Clinton inhaled, as did Monica. It is now major bigtime public record that Monsanto knew all about dioxin and PCBs, reaffirmed by the Washington Post's rewrite of my 1994 article this Jan. 1. Everyone is perfectly aware of 'corporate greed' 'corporate welfare' and companies 'getting away with anything' and that 'you can't trust the government'. Everyone is perfectly aware that Dubya lost the election to Al Gore, but that it's still okay that he's president, and if you think there is hypocrisy being foisted on us, and if you think we're being ripped off, if you remember that Nixon knew, you're just angry, and it's stupid to be angry, so you're stupid too. It's a short way from smart to stupid. Personally, I get the sense of a whole lot of people who just carry that anger inside of them because there is nothing else to do. And then if somebody is angry or acts angry that exposes the denial in everyone else. But it's pointless. What are you going to do? Smash a bank window? The bank would put in a new window, everyone who heard about it would understand why you did it, but would say it was stupid because it doesn't accomplish anything. You might as well make a deposit. Then at least you're saving some money. I was met this morning in the supermarket by photographs of Kenneth L. Lay, with his hand raised to take the solemn oath before the Senate committee investigating Enron, during which testimony he pleaded the Fifth Amendment. This is the provision in the federal constitution which promises that we will not be called as witnesses against ourselves; one cannot be compelled by a court to testify at one's own trial, or by the Senate at one's own hearing. Of course, this provision is mostly for the big guys, since the little guys are given all kinds of statements and confessions to sign, or interrogated for hours until they break psychologically and 'fess up, or are kept in holding cells as detainees forever, until they cooperate. But I'm all for the Fifth Amendment, even if people like Ken Lay get to slime out of what they did. Where I live, people help you out to your car with your groceries. It's a nice human touch, which I refused many times, till I realized that any customer has the power to grant any bagger in the supermarket a ten minute walk outside, after which time I always took up their polite offer to help me to my car. As I opened my trunk to for my groceries, I found a USA Today from an historic moment in the Enron scandal, I don't remember what, and mumbled something about Enron, about which the young woman, named Olivia, helping me out with my groceries, had not heard. She looked at me a little blandly and said she didn't know what I was talking about; she had never heard of Enron. So I gave her the nickel version: a bunch of Texas energy guys, good friends or at least professional colleagues of the president or his family, had ripped off billions in electric fees paid by people in other states, then, in effect, had stolen the retirement savings accounts of thousands of their employees, making off with lots of cash. We chatted a few more moments about scandals. "How frustrating," she said. And I thought, damn. I need a lot more therapy sessions before I can feel this kind of national scandal as simply frustrating and be able to articulate it as such. I must be so overcome with frustration from nearly 20 years of investigating various crimes against the community that I can't articulate the feeling. Frustration, I learned in therapy today, is the combination of anger and helplessness. Oh, that! Looking at frustration in those terms, I've felt it most of my life, especially as a journalist. My gut reaction to today's newspapers, rather than frustration, was something like this. Enron is all about money, people who defrauded the public and supposedly the government, and stole some money. It's good that we seem to care and think it was (in the immortal words of Daffy Duck) despicable. Stealing money (okay, they lied, too, and committed a little securities fraud, but it's difficult to steal honestly) is bad, though we all know these guys are only in trouble because they got caught. We all now they are just an example of what goes wrong. Or do we? Do we look at [name your favorite corporate CEO] and see Kenny Lay? I kept thinking. I want to know where the congressional hearings are for chemical executives who falsify cancer research and push products onto the market that they know make people sick, for profit. We enjoyed day-by-day coverage of the tobacco industry, which was a short-lived triumph. Cigarettes are still more addictive than heroin, so people still smoke them. But when I saw Ken Lay's somber face and his hand floating over his head, in stark contrast to the bold, erect hand of Ollie North, I thought: What about dioxin polluters, PCB manufacturers, plastics makers and the executives of many other industries which knowingly kill people, hide what they do, deceive investigators and make huge profits in the process? How about some congressional hearings for those people? Is being a con artist the only bad thing a person can do? In other words, can you be Hitler if you keep good accounting books? In America, apparently so. Hitler kept pretty good books. He got in lots of trouble, but that was Europe. (True story: Rep. Henry Waxman of California told my editor at Sierra that he would call for congressional hearings into the PCB scandal after my article on the 50-year cover-up of their danger appeared in Sierra in the mid-1990s. But this was pre-empted by some other national distraction. Frustrating.) Reading Joel Kovel's explanation (the guy interviewed in Chronogram magazine, whre this column originates in New York) of capitalism, I felt reassured that there really is something wrong; that somebody can see it and articulate what it is. The system, that is, the network of banks and refineries and factories and processing plants and distribution systems and retail stores, and bomb makers and technology purveyors and the government, can tolerate no shrinkage, he explained. Next year must be bigger than this year; the whole monster must keep growing and consuming, or else it spazzes out. When we shudder at the word recession, a phenomenon widely known to be a drag, which includes layoffs and reduced business activity, we are reacting to the idea of an economy that is getting a little smaller. Not even a lot smaller; not small enough for birds to notice. And I went to bed with this rather frustrating thought: Capitalism and environmentalism really are totally at odds. And, I know I'm a writer and I'm supposed to have a point, but that is my point. And I don't see a way around it.++ |

| Credit: T. A. Rector, B. Wolpa, M. Hanna. Planet Waves logo by Eric, and Via Davis. |