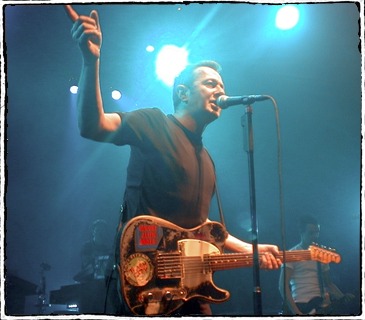

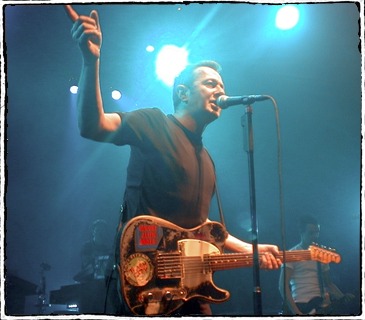

| Rebel Waltz By Constance Perenyi Photo courtesy of Joe's homepage. If I can't dance to it, it's not my revolution.

-- Emma Goldman

This is a belated thank you note. A long overdue love letter. It is also a premature eulogy for a man who died early. No matter when he chose to exit, he would always have been too young. And he was only two years older than I am.

Joe Strummer, front man of the only band that mattered, died on December 22, 2002. The news of his sudden heart attack barely permeated as the radio dj announced the third Clash song of the hour. It is only now, a month to the day later, that I can listen to his voice without denying his mortality.

It is a paradox that Strummer seemed immortal to me, and that of all people I feel compelled to eulogize him as a lover I never met. I heard my first Clash song years ago as I worked through the night in a poorly lit newspaper office. I straightened my tired back and stood at attention as the words "I’m so bored with the USA" blasted across the layout table. I had never heard anything like it. Strummer’s edgy voice pumped right into my veins and set a slow burning fire in my heart.

By the time the first Clash album was released in the U.K. in 1977, I was fully immersed in my own brand of politics and could debate revolution as well as any other radical lesbian feminist. Every month, a small and insanely dedicated group of us put out a newspaper that earned the respect of the far left and the scrutiny of the far right who regularly entered our offices uninvited. We dedicated ourselves to the overthrow of every system that oppressed people whoever and wherever they were. We lived the adage that the personal is political, spent hours debating whether we were Socialists or Communists, and even decided which members could have sex with each other without discriminating against the rest of the collective.

As I describe it now, it sounds as if we were living, breathing caricatures of some archaic political ideal. We were in fact well informed, passionate, and deeply committed to fundamental change. We also took ourselves way too seriously, always a danger when marginalized people suddenly find themselves in good company. As much as I enjoyed the camaraderie, I quickly began to doubt our methods. And there were these two, actually three nagging personal flaws I needed to keep to myself or face expulsion. By the time I encountered Mr. Strummer, I was dangerously, deliriously close to the tipping point.

First off, I wanted to make my living with the art and writing that I so willingly gave away to every left-leaning publication that asked. As I was frequently reminded, that was not exactly a working class aspiration. Better I learn a trade than try to earn money with my own bourgeois talents. But no, I harbored a fantasy of a rewarding life with time and energy to spend in my studio. I even had the audacity to think art could make a difference in the world.

Then there was Strike #2. Despite my best efforts, I could not develop an appreciation of womyn’s culture. Judy Chicago’s airbrushed cunts never warmed mine, and I would happily have incinerated every Chris Williamson and Meg Christian album ever made. Left to my own devices, I tuned the radio to an underground station and listened eagerly for transmissions from the outside world. That’s how I discovered the likes of the Sex Pistols. And how I first fell for Joe Strummer.

And that leads to my third fatal defect. I was not a good man-hater. The party line didn’t exactly spell that out as requisite, but it was always there, sometimes subtly, and often castratingly clear. I stomped and made derogatory comments like everyone else all the while knowing that, oh-my-god, some men were actually attractive to me. It was another dirty little secret to hold close to my perplexed breasts.

Near the end of my collective tenure, I proposed writing a review of Rude Boy, a documentary film about the Clash. All hell broke loose in the planning meeting. It was entirely inappropriate to devote that kind of attention to an all-male band. Besides, their politics were suspect. What else were they doing to change the world besides making music? And weren’t they stealing money from the poor working class slobs who bought their albums and went to their concerts? I argued until I was hoarse and left the office defeated.

Two nights later, Joe Strummer visited me in a dream. He got there just in time to escort me to a collective picnic. Dressed in his characteristic black shirt and pants, he wrapped one arm around my waist and the other around a bucket of fried chicken. We arrived with big grins on our greasy faces and watched my vegetarian comrades scatter like vampires at the foot of a crucifix. And then we committed the ultimate transgression. Joe Strummer lead me into the bushes, stripped me naked, and we fucked joyfully. As I was about to explode in orgasm, I heard one woman scream in horror. She wagged her pale finger in the air and shouted, "You’re out! You’re out!"

Strike three, and oh man was I out. The next day, fully awake and still feeling Joe Strummer inside of me, I officially left the collective to pursue my other passions. I’d love to say that I became a wildly successful artist, found myself a musician lover and lived happily ever after. Only it has never been that easy. I have always asked too many questions, been too political not to struggle with my aspirations and deepest desires. I have been fully human in a world that is suspicious of the real thing. And that is why I still carry a torch for Joe Strummer.

Early on, the Clash was awarded the moniker of "The Only Band That Matters." It was a title rich in irony and self-deprecating humor. And it was true. I wondered then how the music would hold up over time. If anything, it may be even more powerful, more relevant now as the world leans dangerously close to its own tipping point. And the words still makes people stand at attention.

And what was so special about Joe Strummer? He never gave up the good fight. Nor did he ever paint himself into an ideological corner. Even after the Clash fell to pieces and he envisioned other incarnations, he retained a fundamental belief that music was a potent way to affect change. And he carried his convictions with uncommon grace. He was a gentle and compassionate punk.

And in my dreams he was a hell of a lover. Joe, I would dance at the revolution with you any day. Thanks for being. See you again.++

|